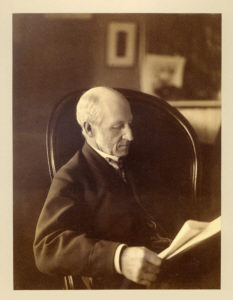

James Elliot Cabot was born June 18, 1821 in Boston. He attended several different schools in Boston and later in Brookline, including G. F. Thayer’s school in Harvard Place. He graduated from Harvard College with an A.B in 1840 at the age of 19, after which he joined his brother, Doctor Samuel Cabot, in Switzerland, and together they traveled in the Apennines before going to Paris to settle down and work at their books. Subsequently, for three years, Elliot Cabot studied German philosophy each winter and took a walking tour each summer, then took his law degree at Harvard Law School in 1845.

A shy man, Cabot found court work daunting, according to his granddaughter, Nancy Cabot Osborne, and he quit after two years. His interest in natural history caused Louis Agassiz, the geologist, to take him along on a scientific expedition to Lake Superior as one of the writers and illustrators of the official report. Examples of his known White Mountain drawings are dated between 1845 and 1847.

Thereafter, he helped his brother Edward, an architect, in his work for a total of twelve years, not counting time out doing civilian service for two years under the Sanitary Commission (a fore-runner of the Red Cross), where he unpacked and repacked stores at the central depot for New England. Although not trained as an architect, he had been given a portion of his parent’s land on Clyde Street in Brookline and designed his house himself. Although he had joined his brother, Edward, to help him with administering the business side of Edward’s architectural practice, he did assist in the design of the Boston Theatre (partly on the site of the present Opera House), and actually built several houses on his own.

He was long a trustee of both the Boston Athenaeum and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, institutions where he volunteered his time. For the Athenaeum he cataloged all their books, and at the Museum of Fine Arts he helped acquire plaster casts of important classic sculpture, since he maintained the museum would never be able to afford any originals.

He was on the Brookline School Committee for nine years, taught briefly at Harvard, first philosophy, then logic, but thought so little of his teaching ability that he quit. Later he became a Harvard Overseer. He was a good friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson, helped him pull together his later writings for publication, and finally, as Emerson’s literary executor, wrote the official biography of him, which was not well received at the time because according to his daughter-in-law, Bessie Cabot, it was not sufficiently adulatory.

He was a writer himself, most days in the last half of his life he disappeared into his study upstairs for long hours to read and write presumably on philosophy. He was an authority on Kant and other German philosophers, but only published a small portion of his writings, some in the short lived “Dial” and others on varied subjects in the “Atlantic Monthly,” which he helped to found. Emerson, in a letter in 1856, remonstrated with him about publishing so little. On his death, his sons made the shocking discovery that he had destroyed all his unpublished writings.

He died from blood-poisoning, caused according to his granddaughter by a cut from an ice-skate. It does seem unlikely that in his eighty-second year he himself would have gone skating, but maybe he got the cut while helping his granddaughter with her skates – a dreadful thought that she never voiced, probably because she adored him. He had no interest in living after his wife died in December of 1901. His son Charles along with his wife, Bessie, and their young daughter, Nancy, moved into Cabot’s Brookline house to keep him company and help look after him until his death just over a year later, on January 16, 1903. He was buried in the Cabot family plot in the Walnut Hill Cemetery, Brookline.

References

New Hampshire Scenery

Cabot’s great, great granddaughter, Nanny Almquist